Kit – Using It, Marching Order

Marching Order (aka 3rd Line)

.

This “how-to” has been a long time coming. I had a draft, with pictures all ready for publishing, but the hard drive I store my documents on died. It’s taken me a significant period of time to get caught back up to where I’m relatively happy (or happier) with the level of detail I need for this article.

.

The introduction to this series of articles (found HERE) outlines the basics and gives a rough idea of where the usage of all this fancy kit lies in the great scheme of things. Now, follow me as we delve deeper into how it’s all meant to be used.

.

Just to be clear, I’m writing this series of articles from the perspective of a light infantryman, or bushwalker/hiker. These roles are somewhat similar, in that they carry their entire house and all essential items for comfortable living on their back for extended periods of time in the bush. In general terms, the same principles of packing and usage apply, but are modified to suit the working environment.

.

As mentioned previously:

– Survive with what is in your pockets.

– Fight with what’s in your webbing (fighting vest or other Load Bearing Equipment).

– Live with what is in your pack.

.

So, it can be seen that the big pack, patrol pack, marching order or Third Line is generally comprised of a backpack (or rucksack, if you will) that has a harness which allows all necessary equipment to be carried in varying degrees of comfort.

Despite the differences between roles (most notably the colour scheme!) such as military users and civilian bushwalkers, the same principles apply for packing loads into rucksacks.

In simple terms, the heaviest items in the pack should be loaded in line with the shoulder blades and as close to the body as possible. Medium-weight items, such as sleeping bags and shelter should be packed as low as possible. Lighter items, such as clothing, should be packed at the top and external surface of the pack.

.

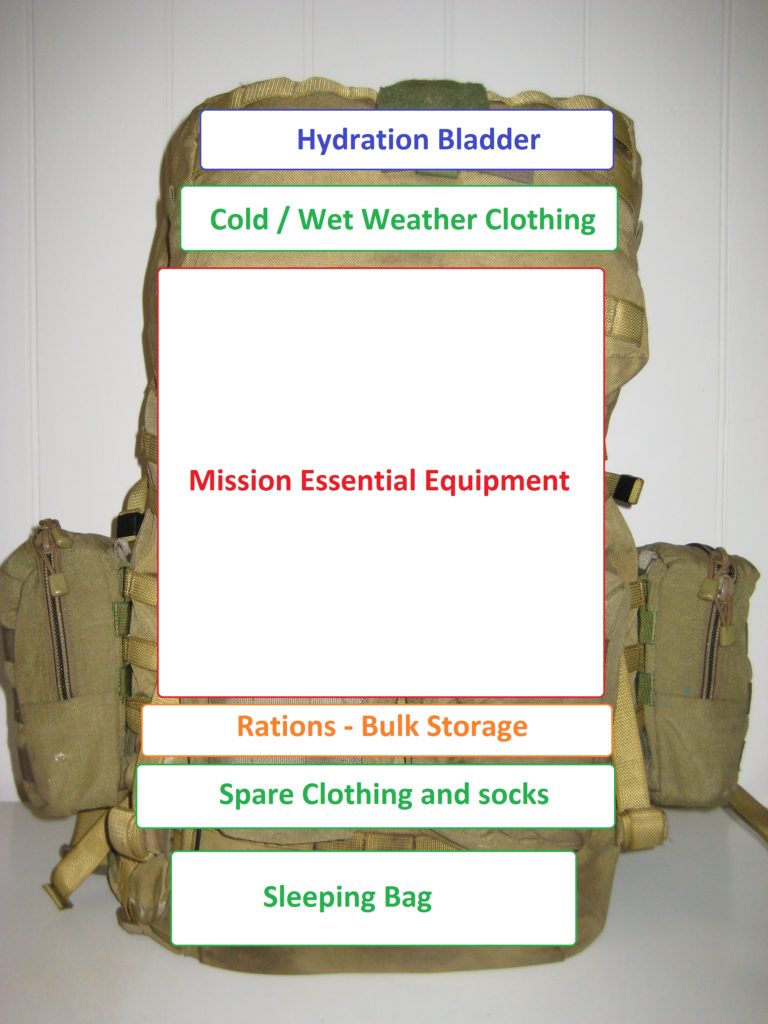

This image is kindly supplied by my good friend Carol Lansdown, who uses it in an exceptional effort to educate school children for outdoor education. It can be used as an excellent reference guide for determining where to pack and stow personal equipment for best balance of the load in safety and comfort. Using her suggestions also provides an excellent guide for convenience of use as well.

.

As Carol’s diagram above clearly demonstrates, the heavy components of the load are stowed as close to the back as possible at shoulder blade level.

Medium weight items are packed at the bottom of the pack, with lightest gear at the top and outside.

It can be seen from this diagram that the average bushwalker can fit all their equipment into the main compartment of their rucksack and live quite comfortably. This is where different end-users vary in their application.

.

For military users, especially those who walk everywhere, such as the traditional light infantryman, there are some extra requirements to consider when it comes to loading up one’s pack. It should be kept in mind though, that the same principles apply – barring such things as unit SOP’s.

.

For those end-users, personal items such as toiletries (or girly bag as they’re known in some circles), water storage canteens and the next meal to be consumed, are stowed exclusively on the outside of the pack.

The reason for this is quite simple: the main compartment of the big pack ‘belongs’ to the platoon commander and section commander (squad leader) to designate which mission essential equipment is carried.

So, this makes life quite simple. The main compartment is generally used for mission-essential kit, and the external stowage of the pack is used for small, personal items.

Consider the following pictures. These are of my Crossfire DG-3, with some external pouches from SORD attached.

.

From the pictures, you can see how the load is distributed.

External layout:

.

Internal Layout:

.

Ok, so that’s how my gear is stowed.

Let’s go into more detail about how and why I have things set up. Please bear in mind, that this reflects my experience nowadays – it’s been a long, painful experience of finding what works for me. I’m no longer bound by military rules or people who may have less experience or knowledge.

.

So what is described below is “A” way of loading a pack, it’s certainly not intended to be “THE” way. But it’s “MY” way….

.

Something to note about my gear: if I consider it valuable, and prefer it to be dry, then the item is stored in some sort of dry container, generally a dry bag as used by bushwalkers. This gives good, redundant water-proofing, unlike having one large dry-bag that can be pierced. This redundancy prevents everything getting wet, and also gives an incidental increase in flotation should creek water crossings be needed.

.

Another small thing I do with my gear is to use colour-coded dry bags for different equipment. So, green dry-bags are for my sleeping bag and shelter. Red dry bags are for extra dry clothing.

Red dry bag used for spare clothing:

.

Green dry bag used for sleeping equipment:

.

Listed below is each area of equipment further explained how I setup and use my gear out scrub. Follow along with me.

.

MISSION-ESSENTIAL STORES –

It’s pretty obvious from attached photos that the mission-essential stores take the largest proportion of the pack. These are often the heaviest items carried as well.

Such items that that have been carried (or seen) will include, but certainly not limited to:

– Manpack radio, or spare batteries.

– Extra ammunition (personal weapon, link for machineguns).

– Explosives and pyrotechnics (M18A1 Claymore, smoke grenades, rocket launchers, flares, mortar bombs, blocks of plastic explosives).

– Defence stores (star pickets, dollies, sandbags, bundles of Dannert wire).

– Hand tools (sledgehammers, shovels, mattocks).

– Power tools (metal detectors, chainsaws).

– Optics (day and night).

– Tripods (for optics or for support weapons).

– Camouflage nets and yowie (gillie…) suits.

– Telephone wire (Don-10) and field telephones.

– First aid supplies.

– Signal panels (VS-17).

– Climbing ropes and harness.

.

All this is often the heaviest portion of the load. It needs to be stowed as close as possible to the back, and in line with the shoulder blades for best balance.

.

It may have to be packed to be easily accessible, yet secure enough not to inadvertently fall out. This is especially applicable for such things as linked ammunition for section/squad machineguns.

.

Stowage of Claymores anti-personnel devices are another factor to consider. Since this is an open forum, I won’t go into how to carry them setup for easy use – if you need to know, seek correct and proper instruction first.

.

Mention should also be made of “assault packs” or go-bags. Depending on unit, mission and tasks, there may be a need to have a very small daypack setup with essentials to carry should the large patrol pack be dropped. Such small bags are great for when mounted in troop carrying vehicles, or carrying extra clothing, ammunition or radios in harsh environments for when the big pack is left behind in a firm base.

.

Such daypacks as the Kifaru E&E (review seen HERE), Source Commander (review seen HERE)or the detachable daypack lid from Mystery Ranch and Crossfire packs are great examples of this.

.

.

WATER –

As can be seen in the pictures, water bottles/canteens are carried as close as possible to the body, inline with the shoulder blades. This is the best location in terms of comfortable and safe carry of the weight, since water will be the second heaviest item in the carried load.

.

This water supply should be used first, leaving water located on the webbing (fighting order) to be consumed last as needed.

You’ll notice that my water containers are a mixture of canteens and bladders. Hydration bladders have come a long way form the leaky, burst-prone fragile things that were available when I first started this journey. However, I only carry a single bladder in the top of my pack to consume during the march or patrol with pack on. I prefer a mixture, as a means to reduce vulnerability if a single container breaks.

.

Please note, that my hydration bladder is stowed at the very top of my pack for ease of access. If using a Mystery Ranch pack (or similar), with a detachable daypack lid, then the water bladder sits in the uppermost pocket.

.

.

SLEEPING –

Sleeping kit is carried in a water-proof stuff sack. Since this is an item that gets brought out of the pack quite often, it’s colouration is somewhat subdued. As a medium-weight item, this kit is stowed at the bottom of the pack. In this case, in the dedicated sleeping bag compartment.

.

My sleeping bag is an old Roman Palm series synthetic fill bag. It rolls up about the same size as a 1L Nalgene bottle. This bag is rated to about 5DegC, which is generally fine for most of the country I walk in below the snow line during the warmer months.

In order to protect the bag from dirt and grime, I have a silk sleeping bag liner. A mozzie net and hootchie complete the ensemble. In colder areas, I substitute the mozzie net for a Goretex bivvy bag.

.

The hootchie has cord attached at all corners for rapid installation. A couple of elastic ockey-straps are also stowed with the hootchie for establishing shelter from the elements.

Something I also do to one of the hootchie cord guylines is a series of knots measuring out common lengths, such as 5cm, 10cm, and 50cm.

My self-inflating mat is stowed at the top of my pack, or where-ever is convenient depending upon mission essential equipment issued. At the top of my pack allows easy access to the mat to use as a seat on short halts.

.

.

ADVERSE WEATHER/SPARE CLOTHING –

The biggest thing to remember when wishing to stay warm and dry in the outdoors is the layering concept. It’s best to carry several thinner, less bulky layers, rather than a single bulky layer.

There’s a couple of reasons for this. Layering allows clothing to be adjusted for weather and activity levels. Sweating in the cold is a bad thing, since drying sweat from clothing will steal all your heat, leading to exposure problems and hyperthermia. Frozen sweat is also a killer, and should be avoided.

.

Several different layers is also more efficient in terms of capturing air layers and pockets of heat to keep you warm.

For most regions in the world, simple layers consist of a merino wool thermal or base layer. A “modesty” or outer layer (such as your clothes or uniform, comprising of a shirt and pants), a fleece jacket (or softshell garment) and a hardshell water-proof and wind-proof layer. Add in extra necessary items such as a beanie and gloves, and this will be more than sufficient for most cold or adverse weather.

Shown is my multicam smock, fleece, and gloves:

.

Green stuff sack used to store cold weather clothing:

.

In really cold or mountainous areas, think about adding a puff layer, such as the Wild Things Parka (seen HERE) or equivalent down lined jacket for extra insulation.

.

Consider also a smock (like the VERTX item seen HERE) in colder climates. This can be used as a lightweight layer on short halts, or during periods of reduced activity when a heavier layer is unnecessary. It also acts as a protective layer to preserve expensive hard layer systems like goretex or eVent rain coats.

.

Stowing this clothing has some considerations. My raincoat sits in the Claymore pouch in the lid of my DG-3. This allows easy access when needed during short halts. It should also be noted that since it is a light item, it is stowed on the outer edge of the pack.

.

Spare clothing, such as socks, jocks (besides thermal underwear, who wears underwear out scrub anyway?) and spare shirt and trousers, should be in another water-proof stuff sack at the bottom of the main pack compartment. Although in my case, since I have the spare room due to my selection of sleep systems, in the sleeping bag compartment of my DG-3. It should be noted however, that a slight re-jig may be necessary should heavier kit for extreme environments be required.

Spare clothing dry bag. Shown is socks, thermal leggings and a merino wool top:

.

RATIONS AND COOKING –

Rations will need to be broken up and distributed into two separate areas.

.

The first area is bulk storage. This is for the next couple of days, but not for immediate consumption. Since rations tend to be medium weight items, they should be placed in the bottom of the main compartment, above the sleeping kit.

.

At beginning and end of every day during admin halts, food for immediate consumption is placed from this bulk storage area to the immediate use area, which is a pouch on the outside of the pack.

.

FIRST AID –

There are two levels to personal First Aid Kits (FAK’s): everyday FAK’s held in the pack which will be discussed in further detail; and Trauma Kits, which are carried in the fighting load to deal with immediate battlefield trauma (gunshot, concussive and other major traumas), and as such, won’t be discussed any further in this article.

.

The everyday FAK (First Aid Kit) is generally geared for self-sufficiency without having to constantly bother people like the platoon medic. Those individuals are already harried and over-worked, and don’t need to be harassed about small things that any grown-up should be able to deal with effectively themselves. Such injuries or afflictions that a personal FAK should be able to deal with is minor strains and sprains, blisters, cold and flu, minor dehydration, cuts and scrapes, and the myriad of other minor things that pop-up whilst living in the field.

.

To this end, the personal FAK should be equipped with:

– Simple pressure bandages (or compression bandages) for such things as snake bite.

– Triangular bandages.

– Sticking plasters, band-aids and moleskin bandages for blisters, small cuts and scrapes.

– Cold, flu and headache tablets.

– Antihistamines.

– Imodium for preventing diarrhoea.

– Tweezers for removing splinters.

– Safety pins.

– Strapping tape.

.

The contents of my First Aid Kit (FAK):

.

First Aid Kit stowed in it’s pouch:

.

Extra items that I throw in my personal first aid kit include Superglue to deal with slightly larger cuts. This is excellent for those cuts in high use skin areas like hands and face where bandages aren’t always effective. At one stage, my nose was held together by superglue and a couple of butterfly strips after a silly self-inflicted injury with my own bayonet – but that’s perhaps a story for another time.

.

Other items include Sting-gose (a topical lotion applied to insect bites to reduce their impact) due to my exotic blood type drawing the little insanity inducers in.

.

TOILETRIES –

Hygienic living in the field is absolutely essential. Rough field conditions mean any small cuts and scrapes can be septic and infected very, very quickly. This means you will want to make sure you pack some basic hygiene items, such as Hand Sanitizer, anti-septic wipes, and any other hygiene products you think might help you to remain clean and bacteria-free. Food hygiene is also vital.

Without practicing basic hygiene, many military forces have suffered far more casualties from disease and infection than from battle against enemy forces.

.

Thankfully though, it’s not too hard to practice basic hygiene whilst living rough. Some simple items and practices are all that is required.

In my Girly Bag, I carry the following:

– Razor.

– Razor blades.

– Shaving brush, generally cut-down.

– 35mm canister of shaving soap (some of you younger blokes from the trendy modern digital camera age may have to Google what a 35mm film canister is).

– Signal mirror (used as a shaving mirror).

– Nail clippers.

– Toothbrush, cutdown.

– Small tube of toothpaste.

– Small micro-fibre towel.

.

Mind you, if I don’t need to shave (especially nowadays wandering the wilds on my own time) then I don’t bother with the shaving kit.

In addition to these items, I carry:

– A bottle of Isocol (rubbing alcohol) which I use in place of foot powder. In addition, it’s great to dash a little over the hands before meals and after personal ablutions.

– A packet of baby wipes. Baby wipes are great for washing armpits, feet and crotch during bird bath procedures every morning.

.

– Iodine water purification tablets.

– A second cups-canteen(or equivalent) for washing and shaving in.

.

– A roll of toilet paper in a water-proof bag. Now, I know toilet paper comes in ration packs/MRE’s, but nice, double ply toilet paper is one of those luxury items I like to carry. Should the task require removal of solid human waste (increasingly prevalent in some national parks nowadays), then extra zip-lock bags and glad-wrap (Saranwrap for all you Americans) should be put in as well. The drills for using Glad/Saran wrap shall perhaps be discussed in a later article.

.

MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS –

– Sewing kit – not just for clothing repair (secondary first aid).

– Iodine based water purification tablets.

– A dedicated bag for carrying rubbish.

– Roll of hootchie cord – used for perimeter/comms cord.

– 90 mile an hour tape – field expedient repairs and first aid.

– Electrical tape.

.

Seen here is a roll of 90 mile per hour tape, sewing kit, roll of hootchie cord and toggle rope.

.

So, there is the theory. The practical application is also essential.

.

It has been noted that personal items are stowed on the outside of the pack, so that water and food on the outside of the pack should be consumed first.

What I mean by this, is that supplies on the main pack should be consumed first, which leaves consumables in the fighting order (or webbing as we call it in the Commonwealth) fully topped up and immediately available should the big pack be dropped for operational or emergency reasons.

This is obviously based on time available to perform daily administrative tasks.

.

Water and meals are taken from the external pouches first. At the end of the day, or during other appropriate administrative periods, then rations and water is transferred from the inner areas of the pack to the outer “ready-use” stowage ready for the next day’s activities.

.

Repair kit of 100 mile an hour tape (duct tape to many in other parts of the world) can be carried wrapped around items such as canteens.

.

Hopefully, this gives some better ideas on marching order.

If you have any tips or hints to share, I’d love to hear them.

Posted in Civilian, Long Range, Military, Packs & Webbing by 22F with 4 comments.

Leave a Reply